As populations continue to grow, demand for mixed-use, accessible, and affordable transit options does as well. Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is a growth model characterized by compact development, a mix of land uses, and multi-modal transportation connectivity. Investments in this infrastructure can catalyze regional growth, improve mobility, and heighten access to opportunity. TOD has many benefits, such as increased mobility options and access to critical services (i.e., childcare, education, healthcare, or employment). Transit access can be essential for low-income households that usually commute by car. Public transit can serve as a backup in the event a commuter’s car is out of commission.

Additionally, research demonstrates the correlation between job accessibility and employment. For example, the National Bureau of Economic Research found that better job accessibility significantly decreases the length of unemployment for certain lower-paid workers who recently lost their jobs. Furthermore, Transit Oriented development can lower overall commuting expenses. The Illinois Housing Development Agency found that households in neighborhoods served by both bus and rail saved an average of $3,000 in annual transportation costs compared to neighborhoods without transit access.

Transit-Oriented Development increases climate-resilient development by reducing greenhouse gasses and the amount of land necessary to accommodate a growing population and economy. A lack of affordable housing within the urban core, however, can push lower-income households farther from the urban core, which leads to exacerbated sprawl, increased travel costs, and more vehicular miles traveled.

Why is equity needed?

Without equity measures, transit-oriented development could be futile because it prices people with lower and moderate incomes out of the opportunity. Due to the racial wealth gap, typically Black and Brown communities are most negatively impacted.

Gentrification remains a growing issue in metropolitan communities across the United States. Equitable Transit Oriented Development (eTOD) accounts for the needs of low- and moderate-income people, often through affordable housing near transit. In Transit-Oriented areas that do not actively promote access and equity, new transit investment or increases in TOD may not attract “core riders.” Core Riders are those who are the most frequent and regular users of transit in an area. They make up a vast majority of the ridership for a community and will likely face the brunt of transit-oriented development measures that don’t include equity. The Dukakis Center research found a majority of transit-rich neighborhoods saw increased public transit use for commuting. Still, the level of use in 40% of neighborhoods declined relative to the broader metropolitan statistical area. This may have been the result of an influx of wealthier residents who don’t rely on public transportation. Attempting to attract these potential riders is not likely to increase ridership if these households replace core riders.

ETOD benefits the municipal economy. Affordable housing in transit-oriented neighborhoods is often multifamily rental housing, which contributes to the density levels that support efficient municipal budgets. In addition, if they live in or near a transportation hub, affordable housing residents can more easily connect to program services and potentially reduce the cost of social service provision for the municipality.

Case Study: Denver

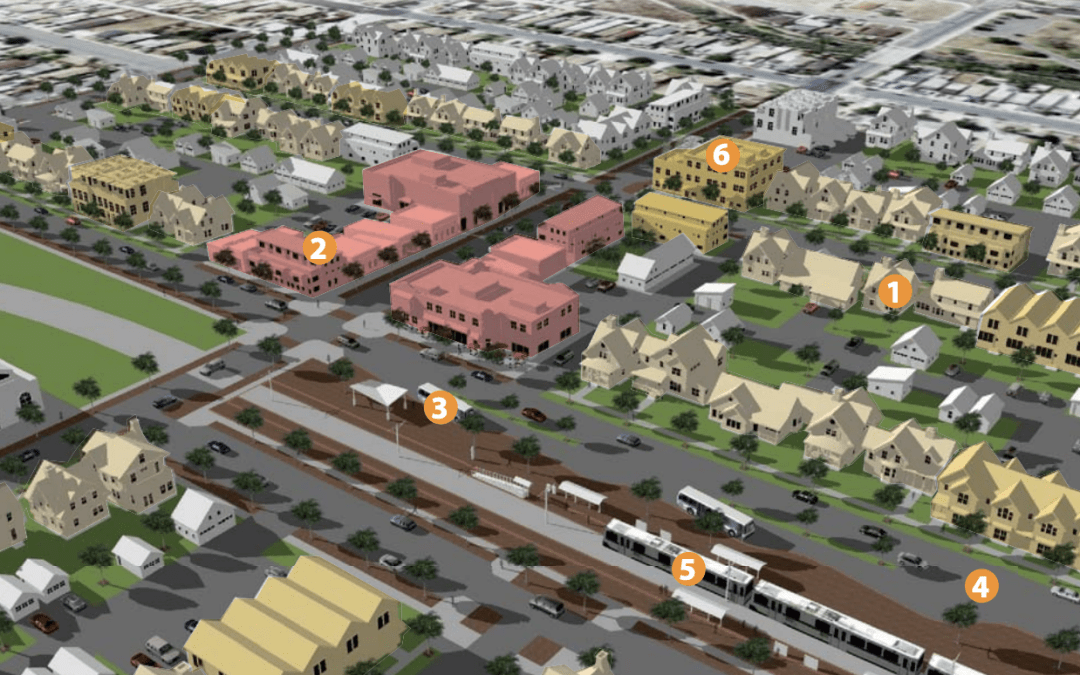

Denver’s transit-oriented development program began in 2006. As of 2016, there were 81 miles of rail lines and over 120 miles of bike paths around the city. To promote eTOD, Denver amended their zoning code and is working with the Regional Transportation Department (RTD), the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), and the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) to implement new regulations. The revised zoning code will limit car use in heavily trafficked areas by limiting mini-storage, drive-thrus, and car washes. To promote climate-resilient development for drivers not ready to relinquish their cars, Denver is working towards requiring electric vehicle charging stations for new commercial development. The city is also examining increasing the price of metered parking to fund transportation infrastructure. Additionally, Denver is creating dedicated transit lanes, higher capacity vehicles to increase the number of people transported, and enhanced stops and stations along transit corridors.

In areas where the city has identified involuntary displacement, Denver is taking steps to mitigate displacements, such as incentives or requirements for on-site income-restricted housing or affordable commercial spaces. The city is creating height bonuses and parking reductions in the zoning code in exchange for income-restricted units in new housing development. Denver will include lower building permit fees for projects that meet the threshold of income-restricted units. Denver aims to create at least 2,000 new affordable units —90% will serve renters, and 10% will serve homeowners.

Denver will make transportation more affordable for riders by including specialized fares or community transit passes. Making transit more affordable also incentivizes residents to use public transit more often. Denver will also work with RTD to create pass programs including a low-income fare program, discounted fair program for youth, EcoPass, Neighborhood EcoPass, and a College Pass program. Denver also encourages RTD to integrate electric and low emissions vehicles into their fleet.

Key Takeaways

The effectiveness of transit-oriented development is limited, without equity measures. Cities should continue to strive for more transit-oriented development to address climate-resilient development within their infrastructure, but in an intentional manner that incorporates the needs of the most vulnerable in their community. Affordable housing near transit hubs and more equitable access to transit are the principal approaches Denver uses to address the negative impacts that have precipitated out of transit-oriented development. Cities can start by taking small-scale steps towards eTOD by reducing ride fares and working toward changes in neighborhood zoning codes.

This article is part of a series from the Land Use Law Center that explores how local governments can implement Climate Resilient Development (CRD) as defined in the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC. CRD requires innovative reform of land use planning and regulation by local governments. The series presents and analyzes numerous local laws and policies capable of adapting to and mitigating climate change to create equitable and sustainable neighborhoods, achieving “sustainable development for all.”

Author: Elizabeth Mazza, 1L Land Use Scholar

Trackbacks/Pingbacks